Every day, energy market analysts comment, systematically and seemingly without any particular rules, on market movements and outlooks (bullish, bearish or stable) with respect to the expected BREXIT type (soft, hard, something in between, etc.) Thus, for example, any negative development on the outlook of the UK leaving with a deal will explain the bullish (or bearish or stable) progression of the day. The same is true for any lack of information or new outlook on this subject: the uncertainty surrounding Brexit will justify the bearish (or bullish or stable) trend of the day!

As we write this, the fateful date of 29 March has passed without the (unpleasant) drama arriving at its conclusion, and everything leads us to believe that many ‘series’ are already in the works. Must we, for all such reasons, delay our analysis of Brexit’s impact on energy markets even further? Here, we’ve taken the liberty of sharing a few reflections with you:

First of all, let’s look at what isn’t changing, or isn’t changing much:

- Customs tariffs:

By leaving the European Union, the United Kingdom will also leave the single market. This switch-over should only have slight consequences for energy markets because both electricity, oil and natural gas are not taxed as part of the WTO agreements. The essentials remain the same!

- Interconnections:

RTE [the French Electricity Transmission Network] and the CRE [French Energy Regulatory Commission] have taken the lead: from 30 March, all capacity allocations are explicit. In practice, this change will only concern daily allocations (other allocations already being made explicit). A change that should therefore only generate a slight (imperceptible) de-optimisation, which will allow for the remuneration of an additional trading activity.

The ETS (European Trading Scheme of carbon emissions quotas), for its part, requires some particular attention, as always:

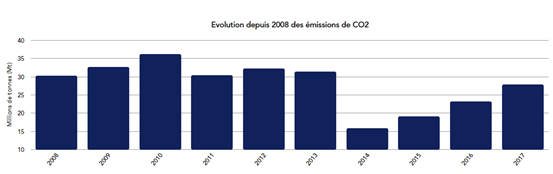

- Strangely enough, the plan for an exit deal envisaged keeping the United Kingdom in the ETS. This would therefore not be the case in the event of a no-deal Brexit. This uncertainty therefore creates great volatility, as the system allows for ‘banking’ (placing allocations in reserve) and ‘borrowing’ (using future allocations), the latter option having been prohibited for British producers with the 2019 allocation freeze. The quota redeeming date for 2018 emissions is 30 April 2019. Should the UK leave the ETS, the banking effect will have bearish results, while the impossibility of borrowing will have a bullish effect (and vice versa, should the UK remain in the ETS. Or perhaps not!)

- Apparently, while 30 April appears at first to be beyond the fateful date, market actors don’t seem to be envisaging the radical scenario in which industry players would decide not to redeem the 2018 quotas. This would certainly contravene existing agreements, but… (the existing framework also permitted borrowing).

Let us now consider the effects on EU policies, since, in the end, this is where the consequences could be even larger. After leaving the European Union, the United Kingdom will no longer carry any weight in the negotiations for building the internal energy market, and Europe will therefore certainly lose a pragmatic and realistic (not ideological) approach to deregulating energy markets, as illustrated in this brief historical reminder:

- Though Great Britain was the pioneer of the obligatory pool system (early 1990s), it didn’t hesitate to abolish it in 2001, judging it to be too manipulable.

- Once it was determined that the ETS did not favour electricity generation using the more environmentally friendly (and often domestic) natural gas over coal (always imported), a floor price for CO2 was established in 2013.

- Generalisation of contracts for difference for low-carbon electricity generation.

- Commitment to nuclear energy: Hinkley Point negotiated in 2014-2015 with a contract for difference.

- Pragmatic (and controversial) policy in favour of shale gas.

- Capacity mechanism launched in 2014.

Indeed, the capacity mechanism question will allow the European Union to bring back good memories of the British: whereas the implementation of this mechanism in the United Kingdom raised no objections from the European Commission on 23 July 2014, the General Court of the European Union, in a ruling dated 15 November 2018 (and with an acute sense of timing), reversed the Commission’s decision not to oppose the aid scheme establishing a capacity mechanism in the UK.

Stay tuned… (the Commission opened an in-depth inquest into the UK’s capacity mechanism scheme on 21 February 2019) but, in the meantime, the European Commission continues to label capacity mechanisms as subsidies, the British capacity mechanism has been halted and, as a result, security of supply in the United Kingdom is compromised…

Philippe Boulanger